Sarah Miles was born in 1941 and is an English theatre and film actress. Her best-known films include The Servant (1963), Blowup(1966), Ryan’s Daughter (1970) and Hope and Glory (1987).

Sarah Miles was born in the small town of Ingatestone, Essex, in south east England; her brother is film director, producer, and screenwriter Christopher Miles. Miles’s parents were Clarice Vera Remnant and John Miles, of a family of engineers; her father’s inability to secure a divorce from his first wife meant Miles and her siblings were born illegitimate.[1] Through her maternal grandfather Francis Remnant, Miles claims to be the great-granddaughter of Prince Francis of Teck (1870–1910), thus a second cousin once removed of Queen Elizabeth II.

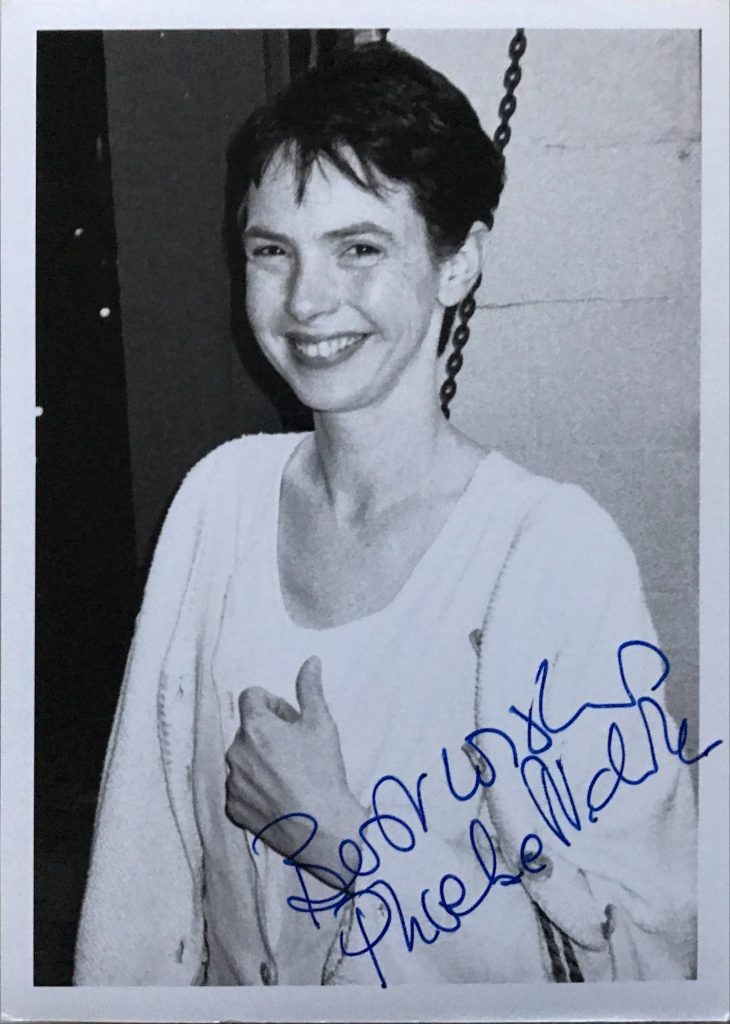

Unable to speak until the age of nine because of a stammer and dyslexia,[5] she attended Roedean, and three other schools, but was expelled from all of them. Miles enrolled at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) at the age of 15. Shortly after finishing at RADA, Miles debuted as Shirley Taylor, a “husky wide-eyed nymphet” in Term of Trial (1962), which featured Laurence Olivier; she was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Newcomer.

Soon afterwards, Miles had a role as Vera from Manchester in Joseph Losey‘s The Servant(1963), and “thrust sexual appetite into British films” according to David Thomson. She gained another BAFTA nomination, this time as Best Actress. She had a “peripheral” part in Michelangelo Antonioni‘s Blowup (1966). At Antonioni’s death in 2007, she referred to him as “a rogue and a tyrant and a brilliant man”.

On 11 February 1973, while filming The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing, aspiring screenwriter David Whiting, briefly one of her lovers, was found dead in her motel room. She was acquitted of culpability in his death. Miles later commented: “It went on for six months. Murder? Suicide? Murder! Suicide! Murder! Suicide! And, gradually, the truth came out, which I’m not going to speak about, but it certainly wasn’t me. I had actually saved the man from three suicide attempts, so why would I want to murder him? I really can’t imagine.”

After acting in several plays from 1966 to 1969, Miles was cast as Rosy in the leading title role of David Lean‘s Ryan’s Daughter (1970). It was critically savaged, which discouraged Lean from making a film for some years, despite her performance gaining her an Oscar nomination and an Oscar win for John Mills, and the film making a substantial profit. In Terence Pettigrew’s biography of Trevor Howard, Miles describes the filming of Ryan’s Daughter in Ireland in 1969. She recalls, “My main memory is of sitting on a hilltop in a caravan at six in the morning in the rain. There was no other actor or member of the crew around me. I would sit there getting mad, waiting for either the rain to stop or someone to arrive. Film-acting is so horrifically belittling.”

Her performance as Anne Osborne in The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea (1976) was nominated for a Golden Globe. Interviewer Lynn Barber wrote of Miles’ appearances in Hope and Glory, White Mischief, and her two earliest films that she “has that Vanessa Redgrave quality of seeming to have one skin fewer than normal people, so that the emotion comes over unmuffled and bare

Filming White Mischief on location in Kenya in 1987, Miles worked for the second and last time with Trevor Howard, who had a supporting role, but was by then seriously ill from alcoholism. The company wanted to fire him, but Miles was determined that Howard’s distinguished film career would not end that way. In an interview with Terence Pettigrew for his biography of Howard, she describes how she gave an ultimatum to the executives, threatening to quit the production if they got rid of him. The gamble worked. Howard was kept on. It was his last major film; he died the following January.

She most recently (2008) appeared in Well at the Trafalgar Studios and the Apollo Theatre opposite Natalie Casey.

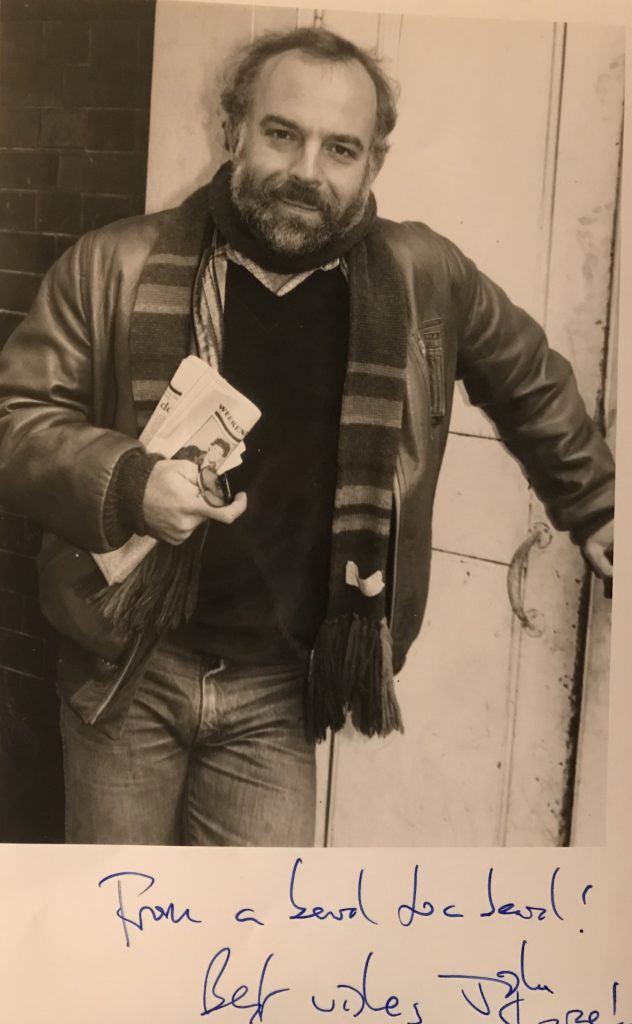

Miles was married twice to the British playwright Robert Bolt, 1967–1975 and 1988–1995. He wrote and directed the film Lady Caroline Lamb, in which Miles played the eponymous heroine, and wrote Ryan’s Daughter, as well. After his stroke, the couple reunited and Miles cared for him. “I would be dead without her”, Bolt said in 1987, “When she’s away, my life takes a nosedive. When she returns, my life soars.” The couple had a son, Tom, who is now a watch dealer